My case for the place of reflective practice in governance

It was great to see an article on best practice in last month’s Boardroom magazine intersecting with a passion of mine – reflective practice and it’s role in business performance.

The article asks the question “what is best practice?” and whether this is creating a static end point for boards to reach – ie once you have ticked the box for best practice, your job is done. It is contrasted to continuous learning where boards always strive to produce better outcomes to fit new circumstances.

In my experience the bridge between these concepts is to add the word ‘current’ before best practice and accepting that we need to keep pace with change. Best practice is only a point in time and we know that how we respond to situations today will be judged differently in the future. Reframing it as current best practice gives us the guidance to make the right decision now, but also the permission to reach a different decision to the same situation at another time.

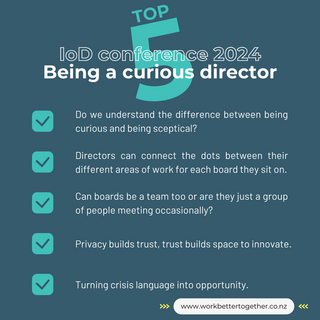

The article describes governance as a dance between learning and contributing for directors, both individually and collectively. It states that for those who are top of their field, it can be hard to question their own reasoning and assumptions and embrace critical reflection. This statement reminds me of a governance mentoring client I work with who realised that the more they progress in their career, the more they have to unlearn in order to step into new opportunities. I think this is a common experience, where directors are selected because of their expertise and career history. However we know the skills that helped them to lead organisations are not necessarily transferable to the board table – where we need to be strategic rather than operational. Sometimes expertise in how it has always been done, does not lead us to think about different possible futures, be truly curious and open to discomfort and challenge. Obviously diversity of thought at the board table helps here, but there is a learning curve for directors to take as they step into a governance career.

The article distinguishes between crystalline intelligence and fluid intelligence, with critical reflection being a marker to use in director recruitment. Critical reflection as a practice however is at odds with the authors’ statement that the pinnacle of skill development and mastery is unconscious competence. As a healthcare practitioner with over 20 years experience of receiving, providing and teaching professional supervision (guided reflective practice) and 8 years on the regulatory board for my profession managing competence and conduct issues, I would argue that unconscious competence can present with the same flaws as static best practice in roles like governance. Being able to effortlessly participate indicates such a level of skill that the conscious brain no longer needs to regulate the activity and learned experience guides the process. However, this does not allow for processing of new information or recognition of existing biases and assumptions which inform the outcome. In my experience, individual critical reflection is best complemented with guided conversations with someone experienced in examining what has happened to date and supporting the person to decide how to proceed in the future. This can surface hidden assumptions, expose patterns of thinking and support the person to learn new strategies.

I agree with the authors’ statement that best practice must be dynamic, but not that mastery is seen as unconscious competence in this context. On boards we must strive to make our performance conscious so we are not working on autopilot with the biases we all bring.

In my opinion, guided reflective practice with an appropriately trained mentor should be a core part of professional practice for directors. There is a wealth of literature on the link to better decision making and performance.

As Ryan (2004) says: “Supervision interrupts practice. It wakes us up to what we are doing. When we are alive to what we are doing, we wake up to what it is, instead of falling asleep in the comfort stories of our clinical routines and daily practice.... The supervisory voice acts as an irritator, interrupting repetitive stories (comfort stories) and facilitating the creation of new stories.”

Perhaps as directors we all need an irritator?

https://www.iod.org.nz/news/boardroom/boardroom-magazine-autumn-2024/what-is-best-practice#